Can't get a tune out of your head? Tina had that for 30 YEARS... only to discover that the cure is surprisingly simple

By Jenny Hudson

|

Scroll down for video

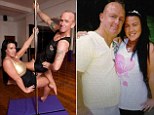

'It's as if the choir is in the room with you,' said Tina Lannin

The tune which pops into your head and won’t go away is maddening enough — but imagine if the music in your head sounded as real as if the musicians were sitting beside you.

Even worse, if the music was discordant, unrecognisable as a tune.

‘It’s

as if the choir is in the room with you and you have no means of making

them stop,’ says Tina Lannin, a 42-year-old from London who suffered

from this for nearly 30 years.

‘One night, I was kept awake by what sounded like a drunken choir singing Away In A Manger.

‘Sometimes it was a rock concert, and sometimes classical music or opera.

'At times there were singers, and at other times, just instruments. But it never sounded right.

'Although it’s music, it’s not harmonious or structured, and usually I couldn’t recognise what it was.’

Tina is describing a surprisingly common condition, musical ear syndrome.

It is a form of tinnitus, a condition that affects one in ten of us.

But while tinnitus is usually a buzzing, ringing or whistling sound in

the ear, without any obvious source, in some people it takes the form of

phantom music.

Around 90 per cent of those with the condition develop it as a result of hearing loss, says Tim Griffiths, professor of cognitive neurology at Newcastle University.

Huw Cooper, consultant

audiologist at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust,

says: ‘We see people every week who report hearing phantom music, and

it’s something that may be under-reported.

‘This is because people are familiar with tinnitus as banging or ringing, but when they hear music, they don’t think of tinnitus. Instead, they worry they are going mad.’

Brain

scans show they are not. In fact, their brain activity during these

hallucinations is very similar to people who are listening to actual

music.

However, with

musical hallucinations, there is no activity in the primary auditory

cortex — the area close to the ear where sound signals are normally

received and then sent further into the brain to be processed, explains

Professor Griffiths.

‘If someone is deaf or loses their hearing, the part of the brain that processes sound signals is deprived of stimulation.

'In the absence of sound, the brain fills in the gaps, as it were, by turning to musical memory for stimulation.’

'Sometimes I would hear buzzing and banging, but frequently it was musical,' said Tina, who is now a professional lip-reader

Usually, in musical hallucinations,

people hear carols and hymns, says Dr Richard McCollum, a psychiatrist

at Devon Partnership NHS Trust, who recently ran an online study

involving more than 500 sufferers.

Intriguingly, the American respondents to the survey typically heard their national anthem.

'Memories laid down early in life with great frequency tend to be most deeply embedded in the subconscious,’ explains Dr McCollum.

‘It is likely to be the case that in America, the national anthem is

more commonly heard, whereas for people in the UK, their deeply embedded

musical memories tend to be childhood hymns and carols.’

He found musical hallucinations tend to start suddenly and intensely.

‘A

typical story is the couple going to bed at night and one saying: “Can

you turn off that music, please?” While the other asks: “What music?” ’

Musical

hallucinations are different from ‘ear worms’ — the songs, TV theme

tunes and jingles that get inside our heads and play repeatedly.

Ear

worms, which affect nine out of ten of us at least once, are caused

when the parts of the brain responsible for processing sound are

persistently activated, for example by a catchy tune heard repeatedly on

the radio, says Professor Griffiths.

In

a musical hallucination, there is also persistent activity, but this

takes place within the brain, rather than being triggered by external

sound.

Another difference lies in the way they are perceived.

‘People

with musical hallucinations initially think what they hear is real. If

you have an “ear worm”, you don’t think it is real,’ says Professor

Griffiths.

‘If you

have an ear worm, it can seem very persistent and difficult to stop, but

your brain will still receive lots of other signals through the

auditory complex and this will eventually “win” over your worm.’

Tinnitus is a condition that affects one in ten of us

Hearing loss that triggers musical hallucinations can be moderate or severe, according to Professor Griffiths’s research.

In some cases, patients lost their hearing suddenly — for example, after a head injury.

Others

had suffered very gradual age-related loss of hearing, although those

with the most severe hearing loss seem more likely to develop musical

hallucinations.

Tina

was born prematurely, and her hearing was profoundly damaged by the

noise of the incubator where she spent her first three months.

By the age of ten she developed tinnitus.

‘Sometimes I would hear buzzing and banging, but frequently it was musical,’ says Tina, who is now a professional lip-reader.

‘It could be a bit creepy. I could tell that inside my head, I was making a rough copy of songs I’d heard before.

'But I always knew it was a part of my tinnitus.’

Why some people develop musical hallucinations after hearing loss, and many don’t, is not clear.

Professor Griffiths believes there may be other risk factors, notably high blood pressure and its effect on the brain.

The theory is this might cause tiny strokes reducing the sound information going to the auditory cortex.

A German study of 11 stroke patients who developed musical

hallucinations showed damage to the part of the brain involved in

processing sound.

Some

people with epilepsy can suffer musical ear syndrome, too, just before

an attack (just as perceptions, such as sense of taste, smell or hearing

can change).

Brain tumours may also trigger musical hallucinations.

Tina’s hallucinations became increasingly difficult to live with.

‘I

became stressed and exhausted trying to concentrate on what people were

saying to me with all the background noise and music going on.’

Tina wore a hearing aid, but when she asked for help, no one seemed interested.

‘I developed my own way of coping,’ says Tina.

‘I learnt that if the music was really annoying, although I couldn’t

stop it, if I concentrated hard on a song I liked better, I could change

the music.’

Like Tina, most sufferers receive little help.

Indeed,

Dr McCollum’s study found that only 16 per cent of people report having

treatment, and just 3 per cent said their treatment was effective.

‘The one treatment known to be effective is increasing the amount of external auditory stimulation.

‘This might be something simple, such as having the radio on more often and avoiding long periods of silence,’ explains Dr McCollum.

‘And if someone has musical ear syndrome after hearing loss, it is important to maximise their hearing capacity.’

This

proved the key for Tina, whose musical hallucinations finally stopped

two years ago after she had a cochlear implant in her right ear.

A cochlear implant is a surgically implanted electronic hearing device.

It bypasses the damaged sections of the ear and directly stimulates the

auditory nerves (a standard hearing aid amplifies sound).

The effect was profound — not only on Tina’s ability to hear but also for her musical hallucinations.

Being close to normal hearing capacity means the over-activity in the

auditory network in her brain is kept in check by sound signals flowing

from the outside world.

‘About four days after the implant was fitted, I woke up to complete silence,’ she says.

‘That was a joy to me, and something I had never experienced before.’

A year later, Tina had a second cochlear implant fitted in her left ear.

‘Now

my musical hallucinations have gone completely. I sometimes get a bit

of buzzing or banging tinnitus, but it is at a much lower noise level.

‘I’ve always loved music, and still do. Now I love piano, particularly Mozart and Beethoven.

'It is much clearer than the music I had in my head, and is a different, enjoyable thing.’

VIDEO: William Shatner speaks on his tinnitus:

-

'No, no, no!' British grandmother, 56, breaks down in tears...

'No, no, no!' British grandmother, 56, breaks down in tears...

-

Bootylicious… meet the 420lb mother of four with the...

Bootylicious… meet the 420lb mother of four with the...

-

Grandmother, 50, lost £70,000 life savings and was left...

Grandmother, 50, lost £70,000 life savings and was left...

-

Careful who you throw snowballs at! Firemen take revenge on...

Careful who you throw snowballs at! Firemen take revenge on...

-

The pub serving pints for a Prince: Charles makes...

The pub serving pints for a Prince: Charles makes...

-

'Hope you and your mate die a horrible death': Dappy trial...

'Hope you and your mate die a horrible death': Dappy trial...

-

Lessons in how not to do customer service: Nightclub...

Lessons in how not to do customer service: Nightclub...

-

The BBC froze me out because I don't believe in global...

The BBC froze me out because I don't believe in global...

-

Big Freeze will last until Friday when the Big Thaw brings...

Big Freeze will last until Friday when the Big Thaw brings...

-

I have killed: Prince Harry reveals he's 'taken a life to...

I have killed: Prince Harry reveals he's 'taken a life to...

-

Internet trolls target academic and presenter Mary Beard...

Internet trolls target academic and presenter Mary Beard...

-

Dental nurse, 25, 'froze to death without shoes or coat...

Dental nurse, 25, 'froze to death without shoes or coat...

i've had tinnitus since i can remeber, when i was a child i had so many ear operation's to try and improve it. but nothing did or has'nt worked. im still in the same situation.

- jennygadsby , kent, United Kingdom, 12/12/2012 16:30

Report abuse