Decision-making ability in young people is independent of IQ

Young people have a general decision-making ability, distinct from IQ, which is associated with good social function, and may be linked to poor mental health, finds a new study led by UCL and Karolinska Institutet researchers.

The decision-making ability, called ‘decision acuity’, is a novel construct and may be underpinned by how strongly certain brain networks are connected, according to the findings published in Neuron.

Lead author, Dr Michael Moutoussis (Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry & Ageing Research and Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology) said: “We worked to improve understanding of the brain underpinnings of decision-making ability in adolescence and early adulthood – a critical period of development and a common time for the emergence of psychiatric disorders. We find that a general factor underpins multiple types of decision-making, which we term ‘decision acuity’.

“People with higher decision acuity do not always make the best decisions, but they opt for specific decisions in a consistent way. Low decision acuity is associated with poorer social function, and may be linked with mental illness symptoms.”

For the study, 830 young people (aged 14 to 24) completed decision-making tasks testing for 32 separate measures, which related to facets such as risk-taking, trusting in other people, and sensitivity to gains and losses.

The researchers found that a common factor underpinned how well people could make decisions, and called this ‘decision acuity’. High decision acuity reflected factors such as fast learning, considering outcomes in the distant future, reward sensitivity, trust in others, and low propensity for retaliation. Independent of IQ, decision acuity predicted performance in the decision-making tasks, was higher in older subjects, and increased with parental education. In addition, decision acuity remained stable over time among 571 of the original participants who were re-tested on the same behavioural tasks 18 months later.

The participants also answered questions about mental health symptoms. The researchers found that high decision acuity was associated with better social functioning, while there were also weak relationships with aberrant thought patterns (including obsessionality and compulsivity) and general distress.

The researchers explain they are as yet uncertain about whether high decision acuity causes improved mental health, or if the relationship may be the other way around, as it may be that poor mental health could affect the development of decision-making ability, or some factor might affect both decision acuity and mental illness symptoms.

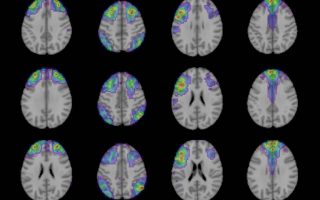

Some (295) of the participants also underwent MRI brain scanning, and the researchers found that decision acuity was correlated with functional (rather than structural) connections between numerous brain regions, including several areas that have previously been linked to decision-making. The researchers replicated the findings when they re-tested 223 participants 18 months later.

Joint senior author Dr Marc Guitart-Masip, who works alongside co-first author Dr Benjamín Garzón at the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, said: “While our study participants here were conducting tasks based on simple decisions, this decision acuity may similarly apply to more complex decisions, as it relates to how far ahead people think into the future and how impulsive or trusting they are.”

Joint senior author Professor Ray Dolan (Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry & Ageing Research and Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology) added: “We do not know yet whether our decision acuity impacts on a risk of mental illness, so further research is needed on this point. This will need to include people with clinical mental illnesses so that we can better identify whether there is a causal link, as well if our findings could influence treatment or prevention strategies for mental illnesses.”

The research team, from UCL, Karolinska Institutet, University of Cambridge, City, University of London, and the University of Zurich, were supported by Wellcome, the Swedish Research Council, the European Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) UCLH Biomedical Research Centre.