Obsessive compulsive symptoms disproportionately affected by the pandemic, study finds

The global COVID-19 pandemic has plunged many of us into a situation of uncertainty and isolation, fuelling a severe psychological challenge for people’s mental health.

Early on, scientists identified spikes in anxiety and depression during lockdown, even among those members of the public without diagnosed mental health conditions. Now, researchers from the Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging and Max Planck Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research have found that obsessive-compulsive symptoms disproportionately increased during the first wave of the pandemic.

“Pandemic fears as well as guidelines are highly relevant to these symptoms,” explains Alisa Loosen, a PhD researcher in the Centre’s Developmental Computational Psychiatry team and lead author of the study. For example, worries revolving around hygiene, contamination, and infection are typical of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a number of studies found that people with diagnosed obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) experienced a worsening of their symptoms during the pandemic.

Research conducted on previous health crises, such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic during the 1980s found that health campaigns could influence obsessive-compulsive symptoms in individuals without any history of psychiatric disorders like OCD.

In the study, published in Translational Psychiatry and supported by the Max Planck Society, Wellcome Trust, and the Medical Research Foundation, Alisa and co-authors wanted to explore how psychiatric symptoms in the general public might change over time and in relation to each other during the pandemic.

“Our study looked at the longitudinal and differential development of investigated symptoms, which is very important when making inferences regarding potential long-term consequences of pandemic-related psychiatric symptom elevations,” according to Alisa.

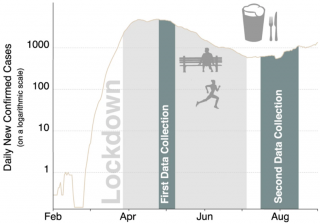

They collected data from 296 members of the public across two time points: the first at the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom from April to May 2020, and the second in July to August 2020, when lockdown restrictions had been lifted.

Participants answered questionnaires about their anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The researchers also collected data about people’s behaviour regarding COVID-19 related information-seeking and how well they had adhered to government guidelines put in place to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus.

They found that anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms were all elevated among the UK public during the peak of the first wave in April 2020. As the virus became less prevalent and lockdown eased, anxiety symptoms stayed the same, while depression symptoms decreased.

However, obsessive-compulsive symptoms rose even further, even when the peak of the first pandemic wave had passed and life had begun to return to normal. Interestingly, these heightened symptoms were not necessarily thematically related to COVID-19: Behaviours such as excessively checking things like locks, appliances, and switches, or obsessive thoughts about harm to self or others also increased.

People with elevated obsessive-compulsive symptoms were also likely to seek out more information about COVID-19. This in turn was linked with a higher adherence to governmental guidelines after the ease of lockdown.

The findings shine a light on the mental health burden of the pandemic, and may help policymakers determine where best to focus resources to help the population recover.

Alisa Loosen said: “This shows that these symptoms need extra attention and should be closely monitored by governmental and public health bodies, which should also provide support to alleviate the general pandemic-related psychological burden to avoid detrimental long-term mental health consequences.”

To understand more about the development of psychiatric symptoms in the general public, the Developmental Computational Psychiatry Team have released the free ‘Brain Explorer’ smartphone app, where users can play brain games for fun and to support their research.

The ‘Brain Explorer’ app is available for anyone aged 9 upwards and you can read more about it here.